SAILING AWAY

Like Ellen MacArthur tacking across the Atlantic Ocean, technology start-up companies pivot around on their journeys, hopefully with the same sense of direction and appreciation for their environments that Ellen exhibits. I am not sure if the analogy is a good one, but tech companies need to be as responsive and flexible as a high performing ocean-going racer in order to respond to the markets they serve.

Matthew Grimes, of Cambridge University, in his recent article in the Academy of Management Journal – ‘The pivot: how founders respond to feedback through idea and identity work’, explores the pivoting phenomena that is recognised as an inherent feature of technology-based start-ups. We hope that this article, reflecting on Grimes’ paper and drawn from our experience at the Alacrity Foundation, provides some useful guidance when managing start-up teams that are pivoting. This article also provides those who might be pivoting some information on what to consider and expect when undergoing a significant change in direction.

The Alacrity Foundation is a demand-led pre-incubator. We form teams and provide them with real life business problems upon which the teams will develop a saleable tech-based business. Although the teams work on demand-led problems, we have, more frequently than not, found that teams pivot away from the original business problem and develop unique solutions that are market focused. When establishing its teams the Foundation’s management have the ability to move founders between different groups. Decisions to move individuals is often the result of the need for technical expertise in a particular team when they have taken a particular technical approach. Changes in personnel also results from personality issues within teams. Perhaps this latter reason is the main cause of team reallocations that the management team have to deal with. Whatever the reason, changes in the composition of a team will result in an individual or a team having to change their perspective: the pivot.

Grimes describes the pivoting phenomena as a ‘creative revision process’ that should not be under-estimated. Grimes identifies that teams need to pivot because of ‘informational deficiencies‘ normally in the spheres of product or market. That is, they either do not have, or cannot obtain, sufficient information on a particular market to allow them to rationalise their current product/business roadmap. At the Foundation we expect teams to rationalise every one of their decisions and actions. We recognise that there is no such thing as perfect market information, but without sufficient verifiable evidence teams will not be allowed to take their product forward.

Objectivity is at a premium in start-ups, but this is an emotional environment. At Alacrity we try to increase the level of objectivity in the decision to develop a technology solution to a particular real-life problem and subsequently a scalable business. We do this by utilising a structured approach to a digital start-up based on the Disciplined Entrepreneurship Canvass developed by Professor Bill Aulet of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This is supplemented by extensive technical and business mentoring and regular in-depth reviews of team and individual progress – there is nowhere to hide!

CREATIVITY IS HIGHLY PERSONAL

The psychological ownership of the business needs to be understood and the impact of an individual or individuals identifying with the product they have been developing cannot be underestimated. Early in their analysis, Grimes notes that ‘creativity is highly personal’ and the motivations of the founders tend not to be instrumental and perhaps rationale from a purely economic based perspective. This is a very useful point, as understanding the motivations of entrepreneurs is essential.

Grimes highlights that pivots can additive or subtractive, that is, they can extend an initial concept or they can reduce, or focus a product’s remit. Again, this can cause personal concern or even confusion. Pivoting results in a sense of loss for those who have invested most in the development of the business. The sense loss can be acute and has to be managed. At the Foundation we spend a significant amount of time discussing change with the teams and individuals to ensure there is understanding and ownership. At Alacrity we have found that focus is imperative for start-ups. Although teams must have ambition and a view to scale their business, the reality is that their first efforts must be focused on persona and beach-head markets. Thus, most early stage pivots at Alacrity usually occur after management/mentor feedback or external validation which requires the team to be subtractive and focus their product with fewer initial features and a narrower market concentration.

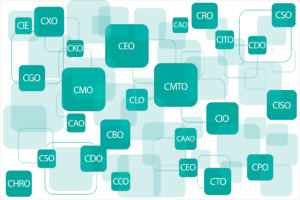

A factor that Grimes identifies which has particular resonance with the Alacrity programme is that people develop socially defined roles related to the work they are undertaking. Once a team pivots, roles can change. Obviously, when we change members of a team, roles will change. This has to be taken into consideration and factored into the reaction to the pivot by an individual. At Alacrity we promote the value of the team. We want our group of founders to create businesses that will scale to a global level. Any changes in a team alters the group identity and ownership. The way we attempt to mitigate against the impact of changes of personnel and roles is to make it clear at the outset and throughout the early stage of the programme that team changes can and will occur. We also spend a significant amount of time talking to individuals and teams about proposed changes. Thus, the Foundation’s management team attempt to build resilience into our teams that balances the need for adaptation and the need to retain a coherent sense of self and purpose. This involves both individual and team mentoring, which must be carefully considered, can be emotionally difficult for all involved and time consuming. Asking a founder to take on a leadership role has caused some problems. Many technical founders do not wish to adopt formal management or leadership roles, although they might have informally adopted a particular position, for example chief technical officer. Others in a team aspire to take on the ‘C-level’ mantel. In fact, we have found some founders that have focused more on their organisational charts where their ‘C-level’ position are clearly defined, than on developing their product and business. The management team spend an inordinate amount of time considering each individual and the composition of the teams.

Grimes identifies three different what they describe as identity-sharpening feedback practices to reappraising one’s psychological ownership of a creative idea, namely: reaffirming; abstracting; and, relinquishing. Following identity-sharpening feedback, Grimes believes that entrepreneurs reappraise their psychological ownership in three different ‘ideas work’ ways: defending; repairing; and re-engineering. Grimes then postulates that entrepreneurs, in response to these competing conceptions of the founder role, adopt three different approaches to identity work: transcending; decoupling; and, professionalizing. This structure is a useful guide to understanding the reactions of founders to change; moving from their psychological ownership, to ideas to identity.

AND FINALLY

Finally, Grimes’ analysis suggests that entrepreneurs’ relative embrace of collective sense-making and differences in their creative experience play a critical role in shaping the creative revision process. This is highly pertinent for the Foundation as we form teams of founders. Collective sense-making is one of the distinctive and most difficult aspects of the Alacrity model. Grimes suggests that entrepreneurs tend to engage in collective sense-making with peers based on their corresponding identification, as a result this encouraged mimetic adoption and validation of similar idea and identity work practices over time: individuals conform to a group think or dynamic. This can be either a positive or a negative dimension. Collective sense-making aids group cohesion and development of a single sense of purpose. It can, however, result in a lack of critical appraisal and creativity.

At the Foundation, we have found a number of high-performing and high-achieving founders are wedded to particular ‘technology platforms’, for example, blockchain, Unity, machine learning, etc., informed by previous ‘creative experience’ This can be either a help or a hindrance. Asking an individual or team to move away from their ‘weapon of choice’ can often cause dislocation and significant discomfort. The psychological attachment to technology can be deep.

Entrepreneurs need to be both reflective and reflexive as their businesses undergo significant change. Grimes states that ‘efforts to incorporate external feedback are central to the process of entrepreneurship.’ This is central to the Alacrity Foundation model. External validation of ideas and technology is vital. Grimes’ paper, building on previous and Grimes’ own research, provides some important insights for those working in and with start-ups. Grimes usefully distinguishes feedback and its impact through the prisms of idea and (personal) identity. They are clearly inter-related but the lack of objectivity witnessed in some start-ups is perhaps more a product of the individual that the idea itself. As Grimes states, resistance to revision is associated with identity-based relationships. Collective sense-making is a complex area. Anyone, like the management team at the Foundation, who deals with teams will understand how multifaceted an area this is.

Pivoting suggests rotating on a single point. Possibly the technology industry should replace the term with tacking. The latter suggests movement and some control and probably better describes the phenomena that we witness in so many of our start-ups . So, as our nascent companies tack their way on their perilous ocean-going adventure perhaps the best advice we can give our teams has been provided by the Roman philosopher, Senenca, ‘If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable.’ Our teams need at least to know where they are going. Where they actually land is, of course, in the hands of the gods.